Rt Hon Harriet Harman QC MP

House of Commons

London

SW1A 0AA

8 March 2016

Dear Mrs. Harman,

I am writing to express serious concerns with regard to the imminent second reading of the Investigatory Powers Bill 2015-16 in the Commons next Tuesday, 15 March.

Those who closely follow issues relating to civil liberties will be aware of the ongoing high-profile case between the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) and Apple Inc. in the United States. In brief, the FBI have requested that Apple write custom software (i.e. software that does not currently exist) to remove data protections in place on a deceased suspect’s iPhone to assist in data retrieval. The FBI and other US agencies have acknowledged that, once created, requests would be forthcoming to use this software on hundreds of additional devices. Apple has filed a motion to vacate the request, citing serious concerns about civil liberties and the right to privacy.

Support for Apple has been registered by way of amicus briefs from amici curiae including Amazon, Google, Microsoft, Facebook, Twitter and dozens of other technology firms, legal professionals, and civil rights organisations suggesting that those who are well-briefed and informed on the technical, legal and civil implications and corollaries of the FBI request are staunchly of the view that the request oversteps the remit of a government agency and represents a threat to, if not the complete loss of, the right to individual privacy.

It is with this background in mind that I would like to express my sincere concerns about the Investigatory Powers Bill (IPB) 2015–16, which I fear will take the UK down a much more sinister path than could be conceived in the US if the Apple motion is unsuccessful. On reading of the IPB as introduced on 1 March, the Bill appears to contain draconian provisions more befitting of a totalitarian regime than a democratic state; it is with deep regret and little hyperbole that I observe that Orwell may have brought a case for plagiarism against the Secretary of State for the draft of the present Bill.

The core IPB issues of Internet Connection Records, bulk data collection and bulk hacking have already been expressed very eloquently and succinctly by the Open Rights Group and the Intelligence and Security Committee and I will express only absolute agreement with their concerns here and refer you to their submission and report published in response to the draft Bill released for pre-legislative scrutiny.

Here, I would specifically like to draw your attention to sections 215–220 (“Additional powersâ€, Part 9 Chapter 1) and 223 (“Telecommunications definitionsâ€, Part 9, Chapter 2) of the Bill as introduced. As with the Data Retention and Investigatory Powers (DRIP) Act 2014 (which has since been ruled unlawful by the High Court after its needlessly expedited passage to Royal Assent in July 2014), Section 223 of the IPB loosens the definition of a telecommunications service to encompass:

“any service that consists in the provision of access to, and of facilities for making use of, any telecommunication system (whether or not one provided by the person providing the service)â€

Where a “telecommunication system†is in turn defined so broadly as to include any:

system […] that exists (whether wholly or partly in the United Kingdom or elsewhere) for the purpose of facilitating the transmission of communications by any means involving the use of electrical or electromagnetic energy

In practice, this is so staggeringly broad that operators of these “systems†include not only telecommunications providers in the traditional sense, but also providers of any service that allows “communications†(encompassing speech, music, sounds, visual images or data of any description) to be transmitted electronically. This thereby includes all “traditional†online applications such as operators of blogs, email services, private messaging platforms, online fora, and social media. But the much greater concern, as noted by the parliamentary Science and Technology Committee, is the inclusion of manufacturers of e.g. connected children’s toys, smart devices and an abundance of other connected services and devices. Notably, the definition extends far beyond existing relevant EU Telecommunications Law.

With the much broader definition in place, the more concerning aspects of the IPB are outlined in Sections 216-218, under which the Secretary of State may serve “national security notices†(Section 216) or “technical capability notices†(Section 217), both of which would impose legal obligations on telecommunication system operators to remove electronic protections (i.e. encryption) with no provision for judicial review of the notices. Indeed, Section 218(8) notes that the recipient of either type of notice “must not disclose the existence or contents of the notice to any other person without the permission of the Secretary of Stateâ€. Failure to comply with the notices will result in the operator facing civil proceedings for a court injunction. The only recourse once a notice is served is therefore for the affected “provider†to appeal the decision with the Secretary of State, at which point the only required action is a review by the Secretary of State-appointed Technical Advisory Board, which has no legal remit and whose decision is not binding.

The implications of the Bill are chilling. In brief, the Secretary of State would have the power to serve a notice on any “telecommunications operator†(with its remarkably broad definition) that a) requires the “operator†to take means to compromise existing security measures b) must not be publicly disclosed c) cannot be subject to judicial review and d) is punishable by civil proceedings if not obeyed. This far-reaching Bill is therefore invasive and oppressive and represents a significant threat to civil liberties in the United Kingdom.

I would therefore like you to represent my concerns to the Commons in the strongest possible terms and oppose the passage of the IPB in its current form, noting at the very least that:

- The IPB is far too broad in its definition of telecommunication systems and operators.

- National security and technical capability notices should be open to judicial review.

- The bulk data collection and Internet Connection Record proposals open the door to mass state surveillance and are in violation of Article 8 of the European Convention on Human Rights.

Nothing less than our right to privacy is at stake.

Yours sincerely,

Richard Pollock

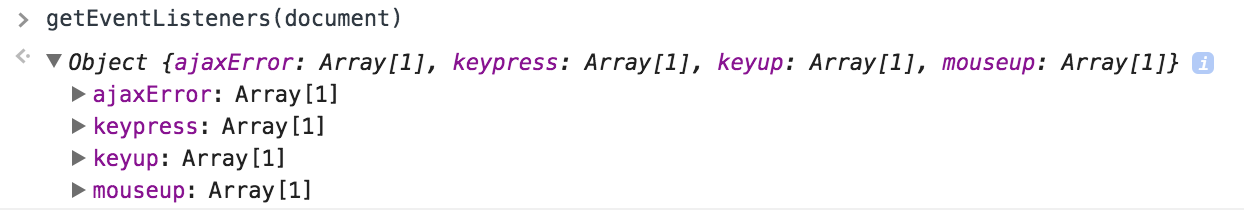

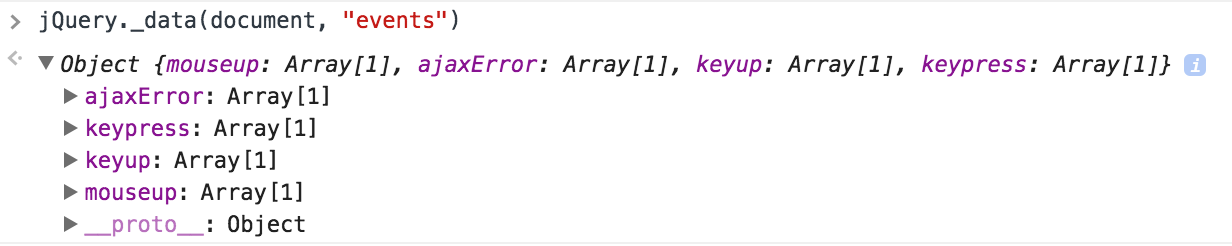

Note that the first argument should be an object conforming to the Element or Document DOM interfaces, rather than a jQuery object or selector (although the raw DOM object can be retrieved using a jQuery selector and dereferencing the first item of the jQuery “array”: $(“p:first”)[0])

Note that the first argument should be an object conforming to the Element or Document DOM interfaces, rather than a jQuery object or selector (although the raw DOM object can be retrieved using a jQuery selector and dereferencing the first item of the jQuery “array”: $(“p:first”)[0])