While Core Data is able to use a SQLite database as its backing store, Cocoa sadly has no native support for full client-server style SQL. Third-party solutions are therefore the answer.

Looking around the web yesterday, I found a number of such solutions including a rather extensive document on OS X ODBC drivers, a rather slick-looking, but wallet-hurting ($700) SQL framework for Cocoa, called MacSQL (it even comes with an Interface Builder palette!) and the open source MySQL-Cocoa project.

ODBC is clearly the compatible, righteous and most open way to access a database, but is also probably the most “heavyweight” solution, which I didn’t really fancy tackling for my humble application. MacSQL looks very nice. The demo movies on their website are a little dated, but show that it really is a very polished solution that allows for a no-code approach to browsing a SQL database. However, it’s also $700 (they do offer a $149 version for hobbyists, but the resulting program can’t be distributed). So, the final option was MySQL-Cocoa.

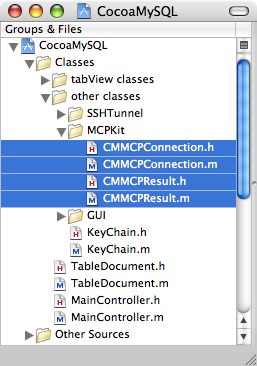

First impressions of the MySQL-Cocoa project might suggest that it’s dead: the examples disk image link on the homepage is broken, the framework doesn’t compile out of the box on 10.4.10 and the latest news item was posted 18 months ago. However, a little searching reveals that a universal binary version of the framework is linked to from this page, hosted by the different, but similarly-named CocoaMySQL project. Excellent.

To use the framework, first download the bundled version and follow Dave Winter’s excellent guide on adding it to your XCode project.

Once that’s done, I found that the easiest way to actually use the framework was to also download the source for Lorenz Textor’s aforementioned CocoaMySQL program and copy these files into your own project:

If the copying’s all gone well, you’re ready to go, so here’s some sample code to get you started. First of all, don’t forget to import the framework and the header files of Lorenz’s files:

#import <MCPKit_bundled/MCPKit_bundled.h>

#import "CMMCPConnection.h"

#import "CMMCPResult.h"

Once that’s done, you’ll probably want to set up a connection and a query result object, as follows:

CMMCPConnection *mySQLConnection;

CMMCPResult *queryResult;

Finally, you can now establish your connection to the database and start querying it, as demonstrated in the following (and, I think, fairly self-explanatory) code:

mySQLConnection = [[CMMCPConnection alloc] initToHost:@"127.0.0.1"

withLogin:@"username"

password:@"password"

usingPort:3306];

if ([mySQLConnection isConnected])

{

NSLog(@"Connected.");

[mySQLConnection setDelegate:self];

[mySQLConnection selectDB:@"databasename"];

queryResult = [mySQLConnection queryString:[NSString stringWithFormat:@"SELECT salary FROM table WHERE department = \"%@\" AND age BETWEEN %d AND %d ORDER BY age",departmentName,lowerAge,upperAge]];

if (queryResult) {

for (i = 0; i < [queryResult numOfRows]; i++) {

[queryResult dataSeek:i];

NSLog(@"%@",[[queryResult fetchRowAsArray] objectAtIndex:0]);

}

}

[mySQLConnection disconnect];

} else {

NSLog(@"Connection failed.");

}

As with my last post, there's no real error checking here, but hopefully the sample code will at least help to get you up and running fairly quickly.