As we learnt yesterday, the release of Leopard will be delayed until October (i.e. 4 months after the end of “Spring” when it was originally slated to ship). Along with this news, developers also received a further development build of Leopard, 9A410, which, according to AppleInsider, ships with a list of almost three-dozen known issues, which are listed here. For the purposes of this post, I’m going to ignore the one or more “top secret” features that are supposed to appear in the final Leopard release and talk about why I think Leopard is taking so long, based on what we know (with a sprinkling of what we think we know)…

What Leopard will bring

Unless Leopard goes the way of Vista and drops support for any of the massive headline features, there will be a huge number of technically-challenging changes in Leopard that push Mac OS X even further ahead of its competitors. So let’s have a look at some of the major ones…

Objective-C 2.0

Welcome to Cocoa 2.0. Objective-C is receiving an overhaul in Leopard. This is not a minor undertaking by any stretch of the imagination. The greatest change is the introduction of garbage-collection, which frees developers from the tedium of manual memory management. Also being added to Obj-C is fast iteration (allowing, for example, traversal of an NSArray without first obtaining an NSEnumerator). Basically, this will reduce this code:

NSEnumerator *enumerator = [myArray objectEnumerator];

NSString stringFromArray;

while (stringFromArray = [enumerator nextObject]) {

NSLog(@"Array content: %@", stringFromArray);

}

to this:

for (NSString *stringFromArray in myArray) {

NSLog(@"Array content: %@", stringFromArray);

}

Nice. Rather brilliantly, Obj-C 2.0 will also introduce “declared properties”, which removes the need to explicity declare methods to access and set properties of your objects. Instead, one simply declares the name of the property and whether it is read-only or also supports writing. Accessing these properties will also be made extremely simple. This:

NSString *name = [myObject getName];

will become, with an appropriate change of the accessor method name, the considerably more readable:

NSString *name = myObject.name;

These changes are very welcome and if, for some reason, you’d rather not use them in your app, they are all opt-in — the Obj-C 2.0 compiler is backwards compatible with Obj-C. So how could this cause a delay in Leopard? I would (perhaps naïvely) imagine that Apple has opted-in to the Obj-C 2.0 runtime for at least some of its programs. We know, for example, that XCode 3.0 takes advantage of garbage-collection. I imagine that, upon rewriting a program to utilise garbage-collection, there is a lot to potentially go wrong, as old memory management code is removed and handed over to the garbage-collector. It’s also possible, although virtually inconceivable at this stage in development, that a problem was detected in the garbage-collector.

Pervasive 64-bit

This is another huge change. 64-bit programs run just fine in Tiger — as long as they’re confined to the UNIX layer. Any UI work had to be either CLI only or through a 32-bit wrapper GUI that communicated with the 64-bit backend. This has all changed in Leopard, which brings LP64 (64-bit Longs and Pointers) support to all application frameworks (except for QuickDraw, Sound Manager and the low-level Quicktime APIs, all of which have been deprecated). Not only this, but there is no 64-bit “mode” in Mac OS X as everything is completely backwards compatible. Programs, frameworks, scripts and even drivers may intermingle with one another, utilising either 32- or 64-bit registers on either PowerPC or Intel processors. Quite an achievement, especially 32-bit driver compatibility, which is something that Windows 64-bit hasn’t yet managed to master.

Why might the addition of pervasive 64-bit frameworks have slowed down Leopard development? Well, adding 64-bit support to all the application frameworks while maintaining backwards compatibility isn’t quite as straightforward as substituting all your ints for longs. Apple has been rather cunning about this whole affair and introduced NSInteger and NSUInteger (U for unsigned) and done the following:

#if __LP64__

typedef long NSInteger;

typedef unsigned long NSUInteger;

#else

typedef int NSInteger;

typedef unsigned int NSUInteger;

#endif

Then they’ve gone through and replaced all unsigned ints with NSUInteger and all ints with NSInteger. Incidentally, they’ve also switched floats to doubles when running in 64-bit which, in the true spirit of “64-bitness”, greatly increases floating point accuracy. This switch is a very good thing, as Cocoa relies on floats for pretty much all of its graphical calculations (distances, colours, etc.). This is all pretty smart, but despite this, there’s still a huge amount of work to do in making sure that all the frameworks are good-to-go and optimised for the appropriate architecture. As a quick example… if you were using this:

NSLog(@"This used to be an int: %d", myInteger);

would you really want to change it to this:

NSLog(@"This is now a long: %ld", myLong)

or just leave it as it was? Take this fairly easy decision and multiply it by the number of times you think integers are used in all of Apple’s application frameworks. I would wager that’s quite a few times. Then there are the considerations about using 64-bit values in applications in more persistent places like Core Data where, more often than not, you don’t really need to store values in 64-bit data types and to do so would just be a waste.

Window Server (resolution independence and Spaces)

Another fairly massive change in Leopard is the introduction of a fully resolution-independent graphics engine. This is no small achievement — Apple isn’t expecting developers to be ready for this until 2008. Resolution independence has become necessary as the resolution of displays has increased considerably since the days of 72 dpi screens and will only continue to increase. Resolution independence removes any assumptions about the resolution of the display. If Tiger were running on two different 17″ monitors, with resolutions of 72 dpi and 144dpi, the interface on the 144 dpi screen would be half the size of that on the 72 dpi screen. This is not the desired effect — it would be preferable for the interfaces to be the same size, but revealing more detail on the 144 dpi screen.

Therein lies one of the difficulties with resolution independence — revealing more detail. In many cases, this is detail that just isn’t there at the moment, as applications tend to use fixed-size bitmap images (just look inside the iLife app bundles for evidence of this). In terms of why this is taking so long, I’d say it’s self-evident: new artwork is required for every icon and custom button in the whole operating system. In each case, Apple may have decided to use vector images or a series of NSBitmapImageReps at different sizes (1x and 4x if they’re taking their own advice).

But there’s not only this massive task to contend with, there’s a lot of altered code as well. As a slightly esoteric example, NSOpenGLView has had to be updated, as OpenGL draws everything in pixels, so the view has to perform an inverse transform on the bounds of the view to convert from pixels to points (which is the coordinate system of the view).

Then there’s Spaces, allowing for multiple desktops, which certainly relies upon Core Animation, but I imagine implementing Spaces also resulted in a non-trivial change to the window server, especially considering the ability to drag windows from desktop-to-desktop from an Exposé-like “show all desktops” view:

Spaces also allows for applications to be “bound” to a desktop, and the Dock (…or LaunchServices or both) is aware of these bindings, such that it will switch to the correct desktop when switching to a different application.

QuickTime and QTKit

QuickTime is receiving a massive overhaul in Leopard as well and QTKit is being pushed forward from its current, rather limited implementation in Tiger. Apple’s also introducing the QTKit capture APIs, which look very sophisticated, allowing simultaneous video capture from multiple USB and FireWire cameras and also simultaneous recording out to multiple devices. More significantly than this, the QuickTime low-level engine is receiving a complete revamp. The goals Apple set themselves for QuickTime in Leopard involved making all QuickTime code parallelisable and 64-bit clean with no remaining QuickDraw code and a code reorganisation to comply with the MVC. Again, this is a huge amount of work, especially as the old QT engine will remain in place (as well as the new one) for compatibility reasons.

Also, although it’s not quite as major, the QT browser plug-in is being given the option to render synchronously in the browser’s paint-loop. This is especially interesting considering the introduction of “alpha” H.264 — H.264-encoded video with an alpha-mask (apparently this is an optional part of the H.264 codec). As another brief aside, QuickTime is also adding support for the display of CEA-608 closed captioning text.

Text handling

Very little information has been released on this front, but the CoreText framework is being made public and Allan Odgaard (developer of TextMate) is excited. This is a big deal. I imagine that CoreText will consolidate some of the powerful features of NSTextStorage, NSLayoutManager, NSTextContainer, NSTextView and make understanding all of this:

a lot easier. This might not seem like a big deal, but there’s a lot of buzz surrounding this new API and, as such, I imagine Apple will be using it in a lot of places, again taking time to make sure it’s perfect (and yes, I know it’s been tested for a long time in Tiger, but expanding it OS-wide still isn’t easy).

Spotlight

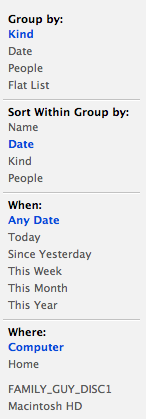

Spotlight’s getting a bit of a revamp as well, allowing searching of networked machines, the use of boolean operators in searches, linking in to the system-wide dictionary to look up search terms and linking in to web search. Spotlight is also now being leveraged by the help system, revealing menu items based on the user’s query in the Help menu.

I don’t know how much under-the hood work is going on in Spotlight for Leopard but, on a side note, Uniform Type Identifiers are being made ubiquitous throughout Cocoa with the introduction of LSItemContentTypes and associated methods. NSWorkspace, NSDocumentController, NSPasteboard, NSOpenPanel and NSSavePanel (amongst others) are being overhauled to support this with new methods being added to NSWorkspace and NSDocumentController. Also, just to produce some example code for all of these changes, Apple has (finally) updated TextEdit to support NSDocument.

Core Animation

The introduction of this framework relies on three technologies already present in Tiger: Quartz, OpenGL, and Core Image. Core Animation is a “layer-based animation system” (formerly code-named Layer Kit), which allows for developers to rapidly add animation effects to their interfaces. It is utilised by Spaces and Time Machine as well as any application that is taking advantage of the new Image Kit or NSGrid views in Leopard. NSGrid views automatically add implicit Core Animation-fuelled animations when reordering, filtering, adding or removing items.

Layers in Core Animation support a variety of attributes and modes, including geometry (allowing 3D transforms), fills, sublayers, borders, CI filters, shadows, opacity, compositing and masking. This, as you can probably imagine, allows for some very complex scenes to be built and animated such as Apple’s now famous “city of album covers” animation. I’m not sure just how long implementing this kind of framework would take, but I’d guess that it wasn’t that easy.

Time Machine

Time Machine is Apple’s new automated backup solution. Conceptually, this is implemented by backing up read-only HFS+ snapshots of the entire file system at a frequency set by the user. So if you want to retrieve a file that was deleted yesterday, Time Machine is able to “point” the application from which the file was deleted to the file system snapshot from the day before yesterday.

Obviously this is only how it works conceptually — only the first backup is actually complete. After this, there is a low-priority back-up daemon that registers to observe file system events. As files change, the daemon notes the changes and coalesces them into one snapshot per day. For files that haven’t changed between snapshots, these snapshots use hardlinks to link to those files in the original backup (or the previous snapshot). This maybe isn’t quite as sophisticated as switching everything over to ZFS, which supports snapshots natively, but I still think there’s a lot of work in there.

And then there’s a whole lot more, including:

- PDFKit, which makes provision for adding, removing and reordering pages to PDFs with no code.

- Upgrade to CUPS 1.2, adding a massive number of new features, including a new web interface for printer administration.

- The implementation of ZFS (although I’m not sure of the extent of the implementation)

- Calendar Store is being added to allow developer access to view and edit user’s iCal events (and To-Do items).

- Multithreaded OpenGL engine and an upgrade OpenGL 2.1 and OpenGL ES 2.0.

- Support for animated desktops using Quartz Composer (which will also support custom patches in Leopard).

- Core image enhancements, including automatic UI generation for CI filters (!) and RAW processing.

- The introduction of Image Kit, including the new Image Browser view (presumable built on the new NSGrid class), the picture-taker panel with support for CI filters, a revamped slideshow view built atop Core Animation, built-in support for image rotation, cropping, scaling, image effects (like those currently in iPhoto) and saving out to multiple formats, etc…

- Massive enhancements to XCode and Interface Builder, such as in-line error messages in the editor and the ability to edit NSToolbars directly in the .nib file. There’s the introduction of XRay, which looks like an incredible tool for monitoring the performance of applications and finding any bottlenecks. And finally, Dashcode will be bundled with Leopard for rapid development of Dashboard widgets.

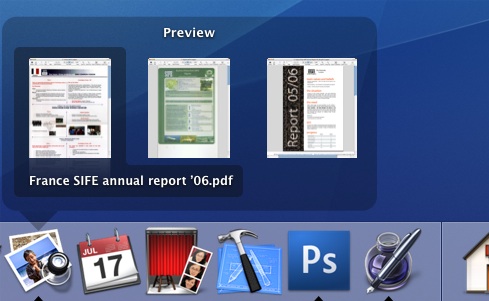

With a few exceptions, I’ve thus far completely ignored any updates to user-level applications and focussed on the under-the-hood changes in Leopard. I’m not going to go through the changes to applications at this time, but from a combination of Apple’s website and various leaked development-build screenshots, we know that iCal, Mail, iChat, PhotoBooth, Preview, Terminal, Automator, Safari and DVD Player have all undergone very significant upgrades. This has presumably taken quite some time as well…

Additionally, there are many changes to system-wide user-level features, such as the introduction of more sophisticated parental controls, greatly enhanced VoiceOver (with Alex the new voice designed for rapid screen-reading), a revamped Sharing preference pane and (somewhat inconsequentially) a whole slew of new screensavers.

And that, ladies and gentlemen, is just a small part of the reason why Leopard is taking so long…