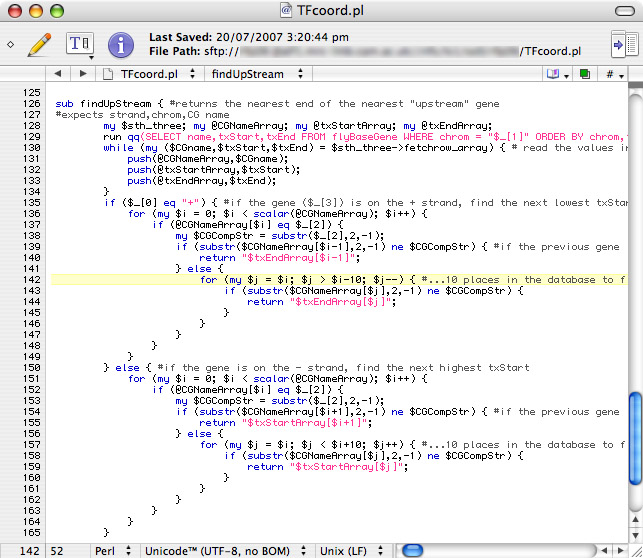

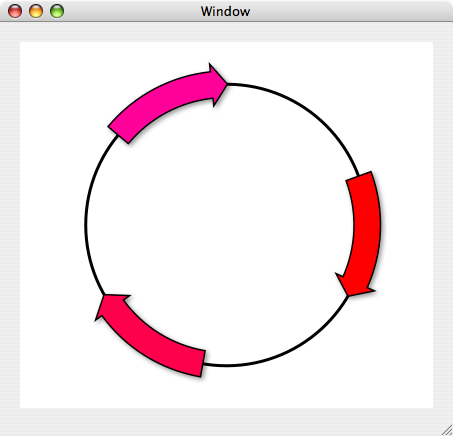

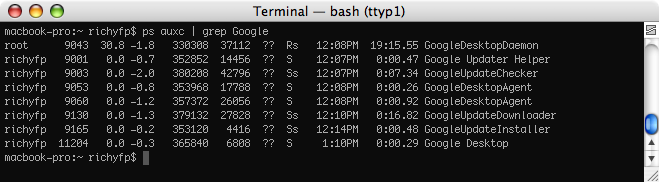

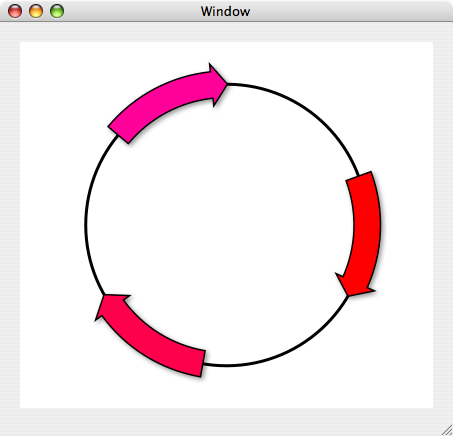

Until a week ago, I had never programmed in Objective-C or used any of Apple’s frameworks, APIs, “Kits” or otherwise. Furthermore, I had never done any object-oriented programming (OOP to its friends) or used XCode to any great extent. My only “real” programming experience was in Pascal (through Delphi) on Windows, a little bit of ANSI C and bits of Applescript, PHP and Python scripting for various purposes. This inexperience meant that I’d also never dealt with memory management thanks to either garbage collection or the simplicity of the programs I was writing. Now, however, I’ve written a Mac OS X native “Cocoa” program that does this:

Brilliant. It even resizes smoothly. But why and how did I do this and does it actually do anything useful?

Why?

I thought it would be a good idea to write a program to help me map out plasmids for my (limited) studies in biochemistry. Plasmids (as you may have just discovered from Wikipedia) are circular pieces of DNA, which are frequently used in molecular biology to insert genes into bacteria to, for example, overexpress a gene for protein purification or amplify a DNA sequence for further cloning. Knowing what genes, promoter sequences, restriction sites and other mysterious bits are in your plasmids is very important. So, I thought, I’ll finally get to grips with Cocoa and Objective-C and write a program to manage a library of plasmids.

How?

Where to start? For some reason, I found (and still find) the concept of object-oriented programming very daunting. I also find Objective-C a very intimidating language, despite it being just a “thin layer” above ANSI C (or, to be more technical, a “strict superset of C” — thanks, Wikipedia). I think I understand the basic principles of it – you write a class which acts as a prototype for instances of that class (of which there may be one or more). Each instance combines data (in instance variables) and methods to access and manipulate that data.

Furthermore, there’s the Model-View-Controller (MVC) architecture to contend with. MVC (admittedly very sensibly) advises that the user interface code and data manipulating code should be separated with a controller in the middle to mediate communication between the two. MVC took me a while to get my head round, until I realised that it’s just like any web application. HTML, CSS and Javascript make up the View, server-side scripts comprise the Controller and the database is the Model. Somehow the client-server divide clears things up for me there…

Anyway, once I’d thought about these new concepts for a bit, I realised that I still had no idea how to actually implement them. For example, how do you actually make a class? Then how do you make an instance (or multiple instances) of that class and, most importantly, just how on earth do things work from then onwards? These are not small questions. I’ll answer a couple of these questions here, just in case a beginner (like me) stumbles across it and finds it useful:

How to make your own class

While it’s technically possible to create your own class from scratch, it’s much easier to leverage a great feature of OO programming called subclassing. Creating a subclass allows you to inherit the behaviour of the class that you’re subclassing (known as the superclass) and then add or modify that behaviour as you see fit. There are two very straightforward ways to create a subclass, depending upon which class you feel fits your needs best:

1. The first way (which can only be used when subclassing NSView, NSDocument or NSWindowController) is to go to File > New File… in XCode and select the appropriate subclass from the “Cocoa” section of the dialog. This will create both the .m and .h files in your project with very little fuss.

2. The second way is to head to Interface Builder and right-click on the class you want to subclass in the Nib-file window, as shown here:

When you select this, a new class, titled “MySuperClassName” appears in the column to the right of the superclass. Right-click on this class, choose “Create files for MyObject”, check the right files are going into the right XCode project and then click “Choose” on the sheet.

Once the files are in place, you can then add the appropriate method and protocol declarations in the .h file and the implementation of these in the .m file. The above methods of subclassing are really just a convenience feature — the real magic involves just sticking this in MYClassName.h:

@interface MYClassName : NSObject {

}

…where MYClassName is a subclass of NSObject. Simple as that.

How to “instantiate” (make an instance of) your class

My OO-beginner roots are about to shine through now; if I’m honest, I’m still not sure what happens at this point, so read on with caution… To actually create an instance of your class, you must use the common Objective-C alloc and init calls as follows:

classInstance = [[MYClassName alloc] init];

First of all, this allocates memory for the instance of MYClassName, initialises its instance variables and then allows this instance to be referred to using “classInstance,” where classInstance was declared at the beginning of the .m file as follows:

MYClassName * classInstance

So I can now pass messages to the instance like this: [classInstance setColor:[NSColor greenColor]], which might turn classInstance green, for example. There is another way to do this, which is to declare classInstance inline as type “id”, which allows the Objective-C runtime to determine which class classInstance is an instance of dynamically (if that made any sense). This would be done as follows:

id classInstance = [[MYClassName alloc] init];

with no need to define classInstance at the beginning of the source file. However, I don’t know whether or not this makes any sense for my purposes…

Rather importantly, there are all sorts of memory management shenanigans that come along with creating instances of objects. These shenanigans include releasing objects when you’re finished with them (or autoreleasing them), which in turn involves such delightful activities as reference counting. I have to say that, at the moment, the prospect of thinking about the “implications of nested Autorelease Pools” (see page 27 of the next link) is very scary indeed. If you do want to know more about memory management on Mac OS X, Apple has some comprehensive documentation here.

Does it actually do anything useful?

Not really, no, but I’m confident that my trusty circle-drawing program will eventually become a functional thing of beauty. Honest. Anyway, I’ve just realised how long this post has become, so I’ll stop here and save some of my exciting adventures through NSBezierPaths, Core Graphics and Quartz for another post…